2021.8.11

When children change, society changes: linking education on an “inclusive society” to the future. The activities of Benesse Foundation for Children.

Ahead of the Tokyo 2020 Paralympics scheduled to begin at the end of August 2021, the phrase “inclusive society” seems to be popping up everywhere recently as people strive to recognize and respect diversity regardless of their awareness of disability sports and the presence of disabilities in society. Leading up to the Tokyo Paralympics, the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) released the latest Japanese version of its “I’mPOSSIBLE” education program online in May 2021. This program was developed by Benesse Foundation for Children in cooperation with the Japan Para-Sports Association, the Japanese Paralympic Committee, and the Nippon Foundation Paralympic Support Center. We talked to the member of staff at Benesse Foundation for Children involved in developing the education program about the thinking behind the program and about their desire to “create materials that help children to realize that everyone has different characteristics and prompts them to think about the structure of society.”

The Japanese version of the program should teach Japanese children the true nature of the Paralympics rather than having them see it as just an event

“I’mPOSSIBLE” is an education program developed with the aim of transmitting the appeal and the value of the Paralympics to children around the world with a view to growing the Paralympic movement. The program has its roots in the success of the 2012 London Paralympics. The "Get Set" education program created for those games is said to have not only changed the thinking and behavior of younger generations, but also caused a raft of changes in society as a whole through its impact on their parents and older generations.

In order to carry on that momentum, the IPC first decided to create an international version of the “I’mPOSSIBLE” education program, and the concept of making a Japanese language version was initiated in 2016 when Tokyo was chosen as the venue for the Paralympics. Ms. Yukari Komatsu (Benesse Foundation for Children), who was involved in the project, talked to us about the background to the development and the creative process.

“The idea was not so much to publicize the Paralympics as an event, but to provide materials to get children thinking about an inclusive society. Benesse Foundation for Children became involved because of our shared belief in the mission to teach and spur thinking about the four underlying values of “courage,” “determination,” “inspiration,” and “equality.” However, we were faced with a variety of issues. It was difficult to get the message over by just directly translating the original international version because, for example, it arranges letters of the alphabet to spell out the four values. Moreover, it was also necessary to put the materials into a form that could be used in Japanese school lessons in order to reach children. To achieve that, we needed to provide guidance for teachers. We tackled each of these problems one by one, and through a process of consulting with our various partners on the project, rather than translating the international version, we began developing a completely new “Japanese version” of the education program in order to more easily communicate the true nature of the Paralympics to Japanese children.

“I previously worked on developing correspondence course materials so I remembered the importance of this step, and first of all consulted with schoolteachers and educational experts to find out what format would work best to get the message over to children. Initially there were a lot of headaches, with the biggest being my own lack of knowledge and understanding of the Paralympics and of people with disabilities. To rectify this, I talked with many Games organizers, athletes, and people with disabilities to learn about their thinking, where they had issues, and what they would like to change about society. As I got a deeper understanding, I was able to reflect this in ideas and suggestions, and the materials began to slowly come together.”

The children’s genuine reactions initially taught me the importance of “awareness”

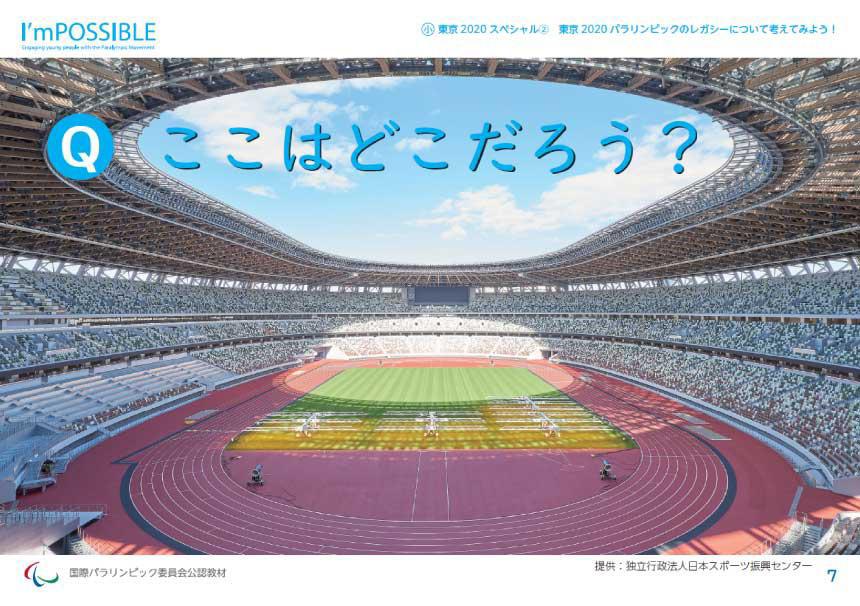

Once the materials had been developed, the Japanese version of “I’mPOSSIBLE” was first rolled out for elementary schools in 2017, with the junior high and high school versions following on later. We gradually varied the content too as time went on, and in May 2021 compiled everything into the latest version that was released online under the title: “Let’s think about the legacy of the Tokyo 2020 Paralympics.”

The Japanese versions of “I’mPOSSIBLE” that have so far been released have been used in a variety of school general learning situations as well as in lessons on physical education, morality, and human rights. Ms. Komatsu was able to watch some of these lessons, and says what left an impression on her was the genuine reactions of the children and how it changed them.

“For example, in a lesson in which they watched video clips of Paralympic athletes and came up with their own catchphrases, the children’s first reaction on seeing a female athlete was “That poor lady,” but once they had seen video of her and heard her speak about her life, one 5th year elementary school boy’s catchphrase was “A beautiful smile earned by never giving up.” Rather than the initial image of people with disabilities being somewhat distant and people to be pitied, by getting to know something about these people the children were able to feel closer to them and get a sense of their individuality. I was surprised by the children’s approach and this really taught me the importance of “awareness.”

What can we do to build a society in which everyone can be happy? Toward a world in which we can think seriously about this.

“At the same time, there were some examples of uniquely Japanese thinking. In one lesson the question was asked “What would you do if a full elevator you were in stopped at a floor where a person in a wheelchair was waiting?” Some of the Japanese children said that even if there were some stairs close by “it’s first-come-first-served, so it’s only fair that the person in the wheelchair waits for the next elevator.” Others said that even if they wanted to give up their place in the elevator, they didn’t think they would be brave enough to actually do it. In contrast, there are some countries where because it is normal to give way to those in wheelchairs and those pushing baby strollers it comes naturally for people to make rational decisions by weighing up the situation, such as “there is no other option for that person apart from the elevator, so you should give up your place to the person in the wheelchair.” It made me aware of the diversity of values.”

“Whenever we came across such differences I wondered where they came from. People with disabilities are normally given “special treatment” in Japan. They tend to be separated from everyone else. Even in schools, children with disabilities are directed toward “special needs schools” and while this enables them to receive special care, it also means they have few opportunities to mix with different people. It severely limits everyone’s chances to see and think about things from a variety of different viewpoints. I believe that change comes from increasing opportunities to know and think about others.”

In conclusion, Ms. Komatsu talked about what kind of society she would like to see after the Paralympics.

“In my opinion, Japan has hitherto been a society that prioritizes the economy and the majority. What can we do to create a society in which people respect each other’s differences and everyone can live a full life regardless of whether they have a disability or not? I want to see a world in which everyone can think and talk openly. At the London Paralympics a change in children’s awareness also affected that of adults. I hope that after the Tokyo Paralympics too we in Japan can move toward a society in which people are more accepting of individual differences and everyone can live happily. My wish is that these materials help play a part in that.”

Article cooperation

Ms. Yukari Komatsu

Office Manager at Benesse Foundation for Children.

Ms. Komatsu has been with Benesse Corporation for a long time, previously working on creating educational materials for elementary schools at Shinkenzemi. After changing workplaces, she moved to Benesse Foundation for Children in FY2016. In addition to working in promotional services to assist children who are economically disadvantaged and those with serious illnesses, she has developed education programs for the Paralympics and promoted information ethics education for elementary schools. She has been in her current position since FY2020.

“I’mPOSSIBLE” Japanese version

https://www.parasapo.tokyo/iampossible/

Benesse Foundation for Children

https://benesse-kodomokikin.or.jp/en/